The Government has published the NPPF1 and it takes effect for all development management decisions from 12 December 20242, whereas for the purposes of plan-making this version of the Framework will generally take effect from 12 March 20253.

In this article Tom Newcombe and Isaac Craft look at some of the main changes made, some of which will be very reliant on guidance yet to be published.

Emphasis on building and councils co-operating

The NPPF reflects the Government’s stated aim that it wants the economy to build, and that building more homes is a key part of that. But is that at the expense of other principles which many consider equally important? It has, for example, removed some wording that focuses on the visual aspect of development: the words “to ensure outcomes support beauty and placemaking”4 have been deleted. What it has not done is weaken the various policies designed to protect the environment, heritage assets or provided wiggle-room regarding BNG or Nutrient Neutrality. It would appear that the Government is more focused on assisting with providing solutions to issues which arise from those requirements, rather than removing them. The Government is also pushing harder for councils to improve working together, and the duty to co-operate remains, but is strengthened. The new NPPF places an emphasis on “effective strategic planning across local planning authority boundaries”.5 It immediately then says that “local planning authorities and county councils continue to be under a duty to cooperate with each other”.6 The NPPF goes on to state that “once matters which require collaboration have been identified, strategic policy authorities should make sure that their plan policies align as fully as possibly”. 7 It then provides detail as to how plans should align.

It also recognises the need for our economy to have development that is relevant to the twenty-first century, it says that the planning policies should “pay particular regard to facilitating development to meet the needs of a modern economy, including by identifying suitable locations for uses such as laboratories, gigafactories, data centres, digital infrastructure, freight and logistics”.8 While this aligns with a trend of expenditure in Government over recent years9, it is a clear statement from Government that it requires local authorities to pay particular regard to this kind of infrastructure.

These additions reflect the recent consultation paper which stated that10 “we are clear that urban centres should be working together across their wider regions to accommodate need” and that “we are not only strengthening the existing Duty to Cooperate requirement but proposing to introduce effective new mechanisms for cross-boundary strategic planning.”

While the bones of the soundness test remain the ‘same’,11 it is important to note, however, that at paragraph 36(a) of the NPPF, the footnote to the “area’s objectively assessed needs” has (in effect) changed due to the amendments in the delivery of the sufficient supply of homes.12 Therefore, when assessing whether the local plans are ‘sound’, and if they have been positively prepared – when relating to housing – the new standard method must be used, not just as a ‘starting point’ (see below).

The Presumption in Favour of Sustainable Development and the “tilted balance”

The consultation draft NPPF proposed changes to paragraph 11 to the NPPF. As expected, changes have made it through to the final version but interestingly they are not the same as those proposed.

One particular change is to paragraph 11(d)(i) by replacing the word “clear” with the word “strong”. Thus, “where there are no relevant development plan policies, or the policies which are most important for determining the application are out-of-date, [LPAs should apply the presumption and grant planning permission] unless: i. the application of policies in [the NPPF] that protect areas or assets of particular importance provides a strong reason for refusing the development proposed; or [..]”. This is a deliberate change giving greater weight to the presumption in the face of conflict with other NPPF policies. There will no doubt be significant debate through PINS and the Courts as to how this affects applying the presumption.

Further, changes sign-posted in paragraph 11(d)(ii) did not come through in the way the consultation draft suggested. Following the statement that if adverse impacts of applying the presumption “significantly and demonstrably” outweigh the benefits when taken against the NPPF “as a whole”, there is now the phrase “having particular regard to key policies for directing development to sustainable locations, making effective use of land, securing well-designed places and providing affordable homes, individually or in combination”. Footnote 9 of the NPPF then specifically lists those key policies as paragraphs 66 (affordable housing) and 84 (isolated homes) of chapter 5; 91 (town centre sequential tests) of chapter 7; 110 and 115 of chapter 9 (sustainable transport); 129 of chapter 11 (density); and 135 and 139 of chapter 12 (design). Whilst this change suggests that these policies are the highlighted ones which would (if breached) defeat permission being granted under a presumption, one must still refer to the words “as a whole”. Thus, other policies in the NPPF remain relevant, but this list merely places extra emphasis on these key policies.

Delivering a sufficient supply to homes

The standard method (first introduced in 2018) identifies the minimum number of homes that a local planning authority should plan for in its area. The standard method as now updated in the practical guidance published on 12 December 202413 (“the Standard Method”) is the nexus to enable the Government to deliver on the envisioned 1,500,00014 new homes during its parliament. Importantly, the Standard Method in the Planning Practice Guidance is no longer an advisory starting point, but mandatory.15 As explained in the PPG, it uses “a formula that incorporates a baseline of local housing stock which is then adjusted upwards to reflect local affordability pressures to identify the minimum number of homes expected to be planned for”.16 There are, of course, exceptions to this rule, one example is if the data required for the model is not available for a local authority area where samples are too small.17 There will be others.

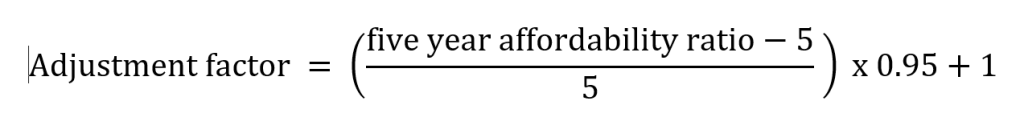

It calculates the minimum annual local housing need figure following a 2-step process18: the baseline is now 0.8% of the existing housing stock, and the data for the most recent housing stock should be used. The Government has published live data of the housing stock split into authorities.19 The second step is to apply an adjustment if the median workplace-affordability ratio20 is above 5. The guidance says “for each 1% the ratio is above 5, the housing stock baseline should be increased by 0.95%”.21 However, it then gives the example “An authority with a ratio of 10 will have a 95% increase on its annual housing stock baseline.”22 There is (thankfully) a formula given in the guidance, as by using the text alone the maths (as written) is not correct. The formula which must be applied is:

That does not give an increase of 0.95% per percentage point over 5 in every case.

The NPPF has now removed arbitrary caps and additions, and the previous paragraph 62, relating to the urban uplift, has been deleted.23 This is one of many changes reversing the change made by the previous Government.

Green Belt and the Grey Belt

To also assist with meeting the 1.5 million housing target, the Green Belt has been reviewed, and this is perhaps the most eye-catching of the changes proposed.

A relatively small amount of the UK is covered by Green Belt, and much of that is covered by other protective designations on top. Green Belt cases are still going to have to be carefully assessed on a case-by-case basis and whilst some of the changes are attractive looking, there are plenty of examples where the consequences of the changes are going to need to be tested, and that will take time. We do still however consider this to be a radical change to one of the most stable of national policies. The fundamental aims of the Green Belt Policy have not changed, and neither have the five purposes of Green Belt. What has changed is a shift towards Green Belt Review by LPAs, the introduction of ‘Golden Rules’ for major development in the Green Belt and the introduction of ‘Grey Belt.’

For a kick-off regarding plan-making, the words that “there is no requirement for Green belt boundaries to be reviewed or changed”24 have been removed. It now says that it “should only be altered where exceptional circumstances are full evidenced and justified”.25 It goes on to list this newly defined term of exceptional circumstances, which includes “instances where an authority cannot meet its identified need for homes, commercial or other development through other means”.26 If an exceptional circumstance exists, then the “authority should review the boundaries in accordance with the Framework and propose alterations to meet the needs in full”.27 The impact of this change is self-evident: most Green-Belt LPAs are going to have to review their Green Belt boundaries. However, if the review provides “clear evidence” that alterations would fundamentally undermine the purposes of the remaining Green Belt, then boundaries need not necessarily be altered.

In addition to the old (para 154) list of development which is not inappropriate in the Green Belt, housing, commercial and other development (i.e. all development?) is now not regarded as inappropriate in the Green Belt where:

“(a) the development would utilise grey belt and would not fundamentally undermine the purposes (taken together) of the remaining Green Belt across the area of the plan,

(b) there is a demonstratable unmet need for the type of development proposed and

(c) the development would be in a suitable location, with reference to paragraphs 110 and 115 of the Framework”.28

Of particular note is a change to 154(g) regarding limited infilling or development of previously developed land. Rather than referring to allowing redevelopment of previously developed land “not having a greater impact on openness or not causing substantial harm” where it would be PDL and is affordable, the test is now just “not cause substantial harm to the openness of the Green Belt.” This is significantly more released and infilling and (non-major) development of previously developed land should now be much easier to achieve.

Grey belt is a new definition, and it is defined as “For the purposes of plan-making and decision-making, ‘grey belt’ is defined as land in the Green Belt comprising previously developed land and/or any other land that, in either case, does not strongly contribute to any of purposes (a), (b), or (d) in paragraph 143. ‘Grey belt’ excludes land where the application of the policies relating to the areas or assets in footnote 7 (other than Green Belt) would provide a strong reason for refusing or restricting development.”29

This is a change to what we had seen in the draft, which used the term ‘limited contribution’30, rather than ‘does not strongly contribute’.31 This is likely to be an easier bar to hurdle.

The term “previously development land” has also been tweaked in the definitions in the NPPF, and “lawfully” has been inserted which will be a welcome change to some, and reference to hardstanding has been included which will be equally welcomed by others and is a significant concession.

Where land is released for development by authorities, the ‘Golden Rules’ for Green Belt development should apply32, and also in the case of major housing development33 and the following contributions should be made:

“a. affordable housing which reflects either: (i) development plan policies produced in accordance with paragraphs 67-68 of this Framework; or (ii) until such policies are in place, the policy set out in paragraph 157 below;

- necessary improvements to local or national infrastructure; and

- the provision of new, or improvements to existing, green spaces that are accessible to the public. New residents should be able to access good quality green spaces within a short walk of their home, whether through onsite provision or through access to offsite spaces.”

- Before development plan policies for affordable housing are updated in line with paragraphs 67-68 of this Framework, the affordable housing contribution required to satisfy the Golden Rules is 15 percentage points above the highest existing affordable housing requirement which would otherwise apply to the development, subject to a cap of 50%. In the absence of a pre-existing requirement for affordable housing, a 50% affordable housing contribution should apply by default. The use of site-specific viability assessment for land within or released from the Green Belt should be subject to the approach set out in national planning practice guidance on viability.”

A development that complies with them should be given significant weight in granting the application.34

In addition to this, and for those sites which perhaps exhibit extraordinary levels of viability, the PPG reminds us that “this 50% cap does not prevent a developer from agreeing to provide affordable housing contributions which exceed the 50% cap, in any particular case.”35

Where development takes place on land situated or released from Green Belt, and is subject to the Golden Rules, then a site-specific viability assessment should not be undertaken or considered for reducing developer contributions, including affordable housing. Otherwise, clearly it will be, although the Government intends to review this ‘Viability Guidance,’ to see if it will make exceptions to this rule.36 Viability is going to become a clear battleground for Green Belt development for some time to come.

It is also of note that in the updated planning policy for traveller sites that the Golden Rules will not apply to traveller sites.37

Transition and Implementation

The new NPPF applies today, but subject to some transitional arrangement in relation to certain provisions, not least the preparation of plans which now apply from 12th March 2025 (unless the plan is at Regulation 19 Stage (and meets at least 80% of housing need) or the plan is at Regulation 22 stage). There might be a temptation (of questionable realism) for LPAs to endeavour to push through local plans – in full haste – to avoid complying with the new Framework. Good luck to any that can, but it should be noted that paragraph 78(c) prevents this from being too much of a concern – from 1 July 2026, where an LPA has a housing supply in a historic local plan which is examined against a previous version of the NPPF, a 20% buffer will be applied where the housing requirement is 80% or less of the most up-to-date need figure calculated under the new rules.

There are other changes which we have not considered, however, it is clear that the new NPPF is an attempt to increase delivery. There is a fundamental need for housing and in particular affordable housing,38 and this is a statement that the Government intend to deliver; whether or not it works is, of course, another matter.

Our verdict? Credit to the Government for being more radical (and faster) than previous attempts. Green Belt changes will be significant, but we cannot see this delivering the 1.5 million new homes required. Changes to affordable housing are minimal and the new NPPF does nothing to address or improve brownfield development or town centre regeneration. The NPPF does very little to address public sector housebuilding which historically has been the only way significant numbers of new housing have ever been built. Ultimately, this still relies on the private sector to deliver; noting issues of resources, costs, viability, and land availability which continue to slow the system, as indeed does resourcing at local authority level. Time will tell what difference these and other changes will make, but one thing is for sure, this is not the last iteration of the NPPF we will see under this Government.

This article is not intended as a substitute for legal advice. Please do contact us if you would like more detail.